A few weeks ago, my Gospel Doctrine class was going over Old Testament Lesson #12: “Fruitful in the Land of My Affliction.” The lesson covers Joseph in Egypt after his imprisonment by Potiphar, his various dream interpretations, and his later reconciliation with his brothers. When discussing the dreams of the imprisoned baker and butler, a class member made the claim that these men had approached Joseph for interpretations because Joseph obviously “had the Spirit” and “was happy.” Nods of approval followed. Disturbed by this line of thought, I raised my hand and said that we do ourselves a disservice by assuming that the Spirit is always accompanied by happiness. This assumption often leads us to question our own spirituality whenever we feel down (i.e., “If I was righteous, I’d have the Spirit and therefore be happy!”). We shame ourselves and each other into thinking we have done something wrong. Not only does this mistake a normal (and healthy) emotion for sin, but it might prevent those suffering from more severe issues (e.g. depression, anxiety) from seeking help. I highly doubt that Joseph was happy about being in prison. However, I pointed out that there is a psychological difference between happiness and meaning.[1] Joseph continued to seek God’s hand both in success and misfortune. His search for meaning is demonstrated later when he says to his brothers, “Even though you intended to do harm to me, God intended it for good, in order to preserve a numerous people, as he is doing today” (Gen. 50:20, NRSV).

A few weeks ago, my Gospel Doctrine class was going over Old Testament Lesson #12: “Fruitful in the Land of My Affliction.” The lesson covers Joseph in Egypt after his imprisonment by Potiphar, his various dream interpretations, and his later reconciliation with his brothers. When discussing the dreams of the imprisoned baker and butler, a class member made the claim that these men had approached Joseph for interpretations because Joseph obviously “had the Spirit” and “was happy.” Nods of approval followed. Disturbed by this line of thought, I raised my hand and said that we do ourselves a disservice by assuming that the Spirit is always accompanied by happiness. This assumption often leads us to question our own spirituality whenever we feel down (i.e., “If I was righteous, I’d have the Spirit and therefore be happy!”). We shame ourselves and each other into thinking we have done something wrong. Not only does this mistake a normal (and healthy) emotion for sin, but it might prevent those suffering from more severe issues (e.g. depression, anxiety) from seeking help. I highly doubt that Joseph was happy about being in prison. However, I pointed out that there is a psychological difference between happiness and meaning.[1] Joseph continued to seek God’s hand both in success and misfortune. His search for meaning is demonstrated later when he says to his brothers, “Even though you intended to do harm to me, God intended it for good, in order to preserve a numerous people, as he is doing today” (Gen. 50:20, NRSV).

This is why President Uchtdorf’s acknowledgement of this truth stood out to me in General Conference:

Being grateful in times of distress does not mean we are pleased with our circumstances. It does mean that through the eyes of faith we look beyond our present-day challenges.

Award-winning playwright Mahonri Stewart had an excellent response to a New York Times article regarding Mormon optimism and great literature. Drawing on some of Mormon’s final thoughts in the concluding chapters of the Book of Mormon, Stewart writes,

Near the end of the Book of Mormon, the narrator, historian, and namesake of one of Mormonism’s most sacred texts, has just witnessed the downfall and near obliteration of his people. As he contemplates the carnage and the waste of potential in the multi-thousands of bodies he sees strewn across the landscape, he laments in a soliloquy worthy of a Shakespearean tragic hero:

O ye fair ones, how could ye have departed from the ways of the Lord! O ye fair ones, how could ye have rejected that Jesus, who stood with open arms to receive you! Behold, if ye had not done this, ye would not have fallen. But behold, ye are fallen, and I mourn your loss. O ye fair sons and daughters, ye fathers and mothers, ye husbands and wives, ye fair ones, how is it that ye could have fallen! But behold, ye are gone, and my sorrows cannot bring your return… O that ye had repented before this great destruction had come upon you. But behold, ye are gone, and the Father, yea, the Eternal Father of heaven, knoweth your state; and he doeth with you according to his justice and mercy. [Mormon 6:17-22]

ones, how could ye have rejected that Jesus, who stood with open arms to receive you! Behold, if ye had not done this, ye would not have fallen. But behold, ye are fallen, and I mourn your loss. O ye fair sons and daughters, ye fathers and mothers, ye husbands and wives, ye fair ones, how is it that ye could have fallen! But behold, ye are gone, and my sorrows cannot bring your return… O that ye had repented before this great destruction had come upon you. But behold, ye are gone, and the Father, yea, the Eternal Father of heaven, knoweth your state; and he doeth with you according to his justice and mercy. [Mormon 6:17-22]

For me, Mormon’s cry of anguish, “O ye fair ones…” is one of the Book of Mormon’s most memorable and haunting passages.[2]

Stewart continues, “I do think there are some uncomfortable truths in Oppenheimer’s article about Mormon culture. One of those truths is that as a culture we do seem to flock away from tragedy.” He notes that “we like to present ourselves in the best light possible, even if it verges on dishonesty. And it can be awfully destructive to those who don’t fit into the unrealistically peppy, idealized “norm” that Mormons are trying to achieve.” He states that there “is definitely a danger in misrepresenting our culture as infallibly happy, as the Little Engine Who Could.” Instead of confronting tragedy, we let ”that pot simmer and boil, until the lid launches off, to a much more disastrous outcome.” It is time to recognize, concludes Stewart,

When our Heavenly Parents and our Lord Jesus Christ looked down at those of us who would become Mormons, to decide what kind of book they would give us, they did not decide to give us a comedy or even a romance. They gave us the Book of Mormon, the story of the downfall of a whole people. They gave us a tragedy.[3]

The Book of Mormon is too often removed from the context of its compilation (if one accepts its historicity). I often think of Mormon’s second epistle to Moroni (Moroni 9) and how it precedes the final chapter of the Book of Mormon. I reflect on the horrors witnessed by Mormon and Moroni. They have seen the evils of their people to the point that Mormon declares, “I cannot recommend them unto God lest he should smite me” (Moroni 9:21). This was all they ever knew; just a constant state of war, destruction, and depravity. This was the context in which Mormon edited the records. It is this context that makes Mormon’s words in 9:25-26 all the more compelling:

My son, be faithful in Christ; and may not the things which I have written grieve thee, to weigh thee down unto death; but may Christ lift thee up, and may his sufferings and death, and the showing his body unto our fathers, and his mercy and long-suffering, and the hope of his glory and of eternal life, rest in your mind forever.

And may the grace of God the Father, whose throne is high in the heavens, and our Lord Jesus Christ, who sitteth on the right hand of his power, until all things shall become subject unto him, be, and abide with you forever. Amen.

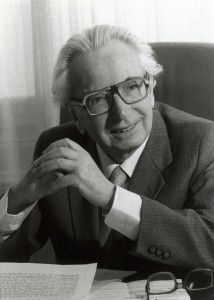

To me, this is what the late psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl calls “tragic optimism”: where “one is, and remains, optimistic in spite of the “tragic triad”…a triad which consists of those aspects of human existence which may be circumscribed by: (1) pain; (2) guilt; and (3) death.” It is saying “yes to life in spite of everything.”[4] This is “optimism in the face of tragedy and in view of the human potential which at its best always allows for: (1) turning suffering into a human achievement and accomplishment; (2) deriving from guilt the opportunity to change oneself for the better; and (3) deriving from life’s transitoriness an incentive to take responsible action.”[5] But Frankl explains that this optimism cannot be forced and that the “pursuit of happiness” is better rendered as the pursuit of a reason to become happy. Yet, this is not an optimism born out of avoidance of tragedy or from cognitive cherry-picking of one’s situation. It comes from finding meaning among the chaos. “Once an individual’s search for a meaning is successful,” writes Frankl, “it not only renders him happy but also gives him the capability to cope with suffering.”[6] Frankl finds that “even the helpless victim of a hopeless situation, facing a fate he cannot change, may rise above himself, may grow beyond himself, and by so doing change himself. He may turn a personal tragedy into a triumph.”[7] This requires us to engage the tragic. This means engaging not only our own suffering, but the suffering of others. “Once the meaning of suffering had been revealed to us,” Frankl recalls,

we refused to minimize or alleviate the camp’s tortures by ignoring them or harboring false illusions and entertaining artificial optimism. Suffering had become a task on which we did not want to turn our backs…There was plenty of suffering for us to get through. Therefore, it was necessary to face up to the full amount of suffering, trying to keep moments of weakness and furtive tears to a minimum. But there was no need to be ashamed of tears, for tears bore witness that a man had the greatest of courage, the courage to suffer.[8]

An oft-quoted passage from the Book of Mormon is found in Mosiah 18. It is invoked as a description of baptismal covenants. Those entering the covenant ”are willing to mourn with those that mourn; yea, and comfort those that stand in need of comfort, and to stand as witnesses of God at all times and in all things, and in all places that ye may be in, even until death…” (Mosiah 18:9). Unfortunately, we tend to skip the mourning and go straight to the comforting, which is interpreted as a kind of buck-up “they’re-in-a-better-place” pep talk. This may be comforting, but not to those who stand in need of it. It is a way for those who are not mourning to comfort themselves: an approach antithetical to what is found in scripture. Comfort comes to those suffering when you show the courage to mourn with them. Truly mourn. It rarely comes from talking about what we expect from life; from reciting the abstract “Plan of Happiness.” Instead, it comes from putting that plan into practice:

We needed to stop asking about the meaning of life, and instead to think of ourselves as those who were being questioned by life – daily and hourly. Our answer must consist, not in talk and meditation, but in right action and in right conduct. Life ultimately means taking the responsibility to find the right answer to its problems and to fulfill the tasks which it constantly sets for each individual. These tasks, and therefore the meaning of life, differ from man to man, and from moment to moment. Thus it is impossible to define the meaning of life in a general way. Questions about the meaning of life can never be answered by sweeping statements. “Life” does not mean something vague, but something very real and concrete, just as life’s tasks are also very real and concrete. They form man’s destiny, which is different and unique for each individual. No man and no destiny can be compared with any other man or any other destiny. No situation repeats itself, and each situation calls for a different response.[9]

ourselves as those who were being questioned by life – daily and hourly. Our answer must consist, not in talk and meditation, but in right action and in right conduct. Life ultimately means taking the responsibility to find the right answer to its problems and to fulfill the tasks which it constantly sets for each individual. These tasks, and therefore the meaning of life, differ from man to man, and from moment to moment. Thus it is impossible to define the meaning of life in a general way. Questions about the meaning of life can never be answered by sweeping statements. “Life” does not mean something vague, but something very real and concrete, just as life’s tasks are also very real and concrete. They form man’s destiny, which is different and unique for each individual. No man and no destiny can be compared with any other man or any other destiny. No situation repeats itself, and each situation calls for a different response.[9]

In a quote he attributes to Dostoevsky, Frankl writes, ”There is only one thing that I dread: not to be worthy of my sufferings.”[10] When we ignore suffering or attempt to gloss over it, we hinder the progression of ourselves and others. We bury our ability to empathize. “Suffering is an ineradicable part of life, even as fate and death. Without suffering and death human life cannot be complete. The way in which a man accepts his fate and all the suffering it entails, the way in which he takes up his cross, gives him ample opportunity – even under the most difficult circumstances – to add a deeper meaning to his life.”[11] To engage suffering, to mourn with those who mourn, is to love. “The truth – that love is the ultimate and the highest goal to which man can aspire. Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of man is through love and in love.”[12]

Tragic optimism provides a way for we Mormons to put away the constant (if unintended) “all is well in Zion” (2 Ne. 28:21) that often escapes our lips in the midst of suffering. Perhaps it will also help us avoid the consequences of these actions: “…and thus the devil cheateth their souls, and leadeth them away carefully down to hell.”

NOTES

1. Roy F. Baumeister, Kathleen D. Vohs, Jennifer L. Aaker, Emily N. Garbinsky, “Some Key Differences Between a Happy Life and a Meaningful Life,” Journal of Positive Psychology 8:6 (2013): 505-516. See also Emily Esfahani Smith, “There’s More to Life Than Being Happy,” The Atlantic (Jan. 9, 2013): http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/01/theres-more-to-life-than-being-happy/266805/; Jill Suttie, Jason Marsh, “Is a Happy Life Different from a Meaningful One?” Greater Good (Feb. 25, 2014): http://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/happy_life_different_from_meaningful_life

2. Mahonri Stewart, “Behold, Ye Are Fallen: The Case for Mormon Tragedy,” Dawning of a Brighter Day (Nov. 19, 2013): http://blog.mormonletters.org/?p=6972

3. Ibid.

4. Viktor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning, Revised and Updated (New York: Washington Square Press, 1984), 161.

5. Ibid., 162.

6. Ibid., 163.

7. Ibid., 170.

8. Ibid., 99-100.

9. Ibid., 98.

10. Ibid., 87.

11. Ibid., 88.

12. Ibid., 57.