*Author’s Note: An earlier version of this address was presented at the annual Mormon Scholars in the Humanities conference, March 15, 2013 at Brigham Young University.

The Latter-day Saint temple endowment is a taboo topic for reasons obvious to probably most people in this audience. Culturally, the ordinances performed in Mormon temples are deliberately exclusive, open only to individuals who meet the requirements necessary to participate. Within these rituals, participants promise not to reveal the sacred nature of the ordinances to outsiders, thus forming a communicative kinship through the shared knowledge of divine secrets. It is not my intention to trivialize the reverence that Latter-day Saints, including myself, have for the endowment, but rather, to identify and define a few of the underlying rhetorical implications the endowment presents for initiates and outsiders alike.

Before moving forward, it is important to explain what I mean by the term “rhetoric.” In my field, it’s common to hear my associates cringe at the use of the term “rhetoric” in contemporary discourse. The late Hugh Nibley, who appropriately earned the nickname “Poor Man’s Plato” (Petersen, 2002, p. 261), described rhetoric as “the landslide of vulgarization [that] once started could not be stopped” (Nibley, 1956, p. 68). Plato’s scathing critiques of rhetoric in the Gorgias and the Phaedrus characterize it as a fraudulent, flattering craft; a form of discourse that dresses up bad ideas with eloquent language to lead commoners astray. Plato saw the paid, itinerant rhetoricians of his day as a threat to his own livelihood. It is likely that many of his claims against rhetoric were exaggerated, since much of what we know about ancient rhetoric before Aristotle comes almost exclusively from Plato’s dialogues.

Plato’s negative depictions of persuasive speech as “mere rhetoric” are prevalent today. More often than not, the word is used to portray shallow, bombastic, pandering, and “dubious” speech used to “deceive and exploit” the masses (Dues & Brown, 2004, p. xviii). After all, that’s what the other side in Congress always does, but never our side. For modern students of rhetoric, however, it is not the monster Plato crafted from straw. Taking cue from Aristotle (2011) many scholars of classical rhetoric define it as “the faculty [dunamis] of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion” (p. 4). For me, rhetoric is a neutral tool that extends to all forms of symbolic, persuasive communication.

Classical rhetoric makes ready use of Aristotle’s three artistic proofs, ethos, pathos, and logos. Simply defined, ethos in persuasion refers to character appeals designed to influence another person’s attitudes or actions. Pathos is the use of emotion and general passion to bring about a shift in thinking, while logos refers to the use of inductive and deductive reasoning to both advance one’s own arguments and to dismantle the positions of opponents. Given these definitions, I believe that Latter-day Saints undergo a fundamentally persuasive experience when participating in the temple endowment. I call this experience mystical rhetoric, first because of its emphasis on experiencing Deity through symbolic, nonverbal communication, and second, because the covenants initiates make oblige them to live a life in compliance with divine directives.

Though the most basic elements of the modern endowment can be traced back to early Mormon history, a number of faithful Latter-day Saint scholars have sought to establish ancient origins for temple ordinances. These scholars point to allusions in the New Testament, pseudepigraphal writings such as the Forty-Day literature, and even the accounts of Christ’s post-resurrection ministry in the Book of Mormon. Andrew Skinner advances this claim in a 2010 paper published in the Maxwell Institute’s Studies in the Bible and Antiquity entitled “The Dead Sea Scrolls and the World of Jesus.” Skinner argues that Acts 1:3 provides a possible link to the claim that Christ instituted a series of exclusive, secret rituals (p. 67). The King James translation of the verse reads that Christ used the forty-day ministry to teach by “infallible proofs . . . the things pertaining to the kingdom of God.” Appealing to the Greek text from which the verse was translated in the Authorized Version, Skinner notes that the word translated as “infallible proofs” is tekmēriois, meaning literally “sure signs or tokens” (p. 67).[1]

If an ordinance like the endowment existed in the early church, and if that ordinance is being referenced by Luke’s use of “infallible proofs” in the Acts, its underlying premise, like that of the LDS endowment, would still be rhetorical. As mentioned before, Aristotelian rhetoric makes use of three artistic proofs, or in Greek, entechnoi pisteis. Proofs lay out the arguments supporting a given thesis or idea based on what is most probably true. The proofs are thus the source material, the means by which one witnesses a rhetorical demonstration and is transformed from being an unbeliever to a believer. If Skinner is correct in arguing that Acts 1;3 is alluding to an endowment-like ordinance in the early Church, I theorize that these “sure signs or tokens” are likely an imitation of an even earlier story in the New Testament.

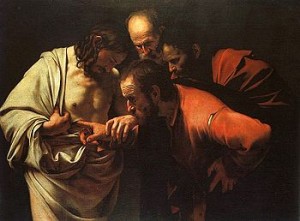

Upon hearing of Christ’s postmortal appearance among his fellow Apostles, John writes that Thomas immediately questioned the veracity of the account. Having likely witnessed the crucifixion personally, Thomas expresses his evident skepticism by proposing a hypothetical enthymeme. “Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands,” he says, “and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe” (John 20:25 NRSV). A week later, as John’s account states, Christ miraculously appears in a home where the disciples had met in secret. In a recreation of his appearance on Resurrection Day, where Christ invited the other disciples to feel the nail prints in his hands and the wound in his side, Jesus asks Thomas to come forward. Offering his hand as a tangible proof of his resurrection, Christ invites Thomas to “put your finger here, and see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it in my side. Do not doubt, but believe” (John 20:27 NRSV). By requesting that Thomas feel the tangible wounds of the crucifixion, the proofs of Christ’s resurrection are made evident to the doubter. Jesus persuades Thomas to believe through the sure signs and tokens by which he “shewed himself alive after his passion” (Acts 1:3 KJV). Through this reenactment of Christ’s post-resurrection appearance on Easter Sunday, Jesus allows Thomas to join an exclusive community of witnesses.

Regardless of whether the modern temple endowment is a restoration of ancient Christian rituals or a product of Joseph Smith’s vision for a new religious order, the modern ordinance is used as a gate by which Latter-day Saints also enter into a privileged community of believers, united by the shared knowledge provided in the language of the endowment itself. Initiates who are exposed to the endowment are introduced to terms and phrases that are largely unique to Mormonism. This shared terminology fits within the framework of what rhetorical critics call “code words.” Writing on the potential for such language to unify and stabilize certain groups, Hart and Daughton (2005) note that code words act as a “token that can be shared with new members of a group to make them feel included” (p. 158). Furthermore, “those who have not learned” the message “or who cannot use it with authority are denied its riches” (p. 159).

There is strong evidence to suggest that Joseph Smith adapted elements of his own environment to convey certain ideas through the endowment. As Matthew Bowman (2011) writes, Joseph was introduced to Freemasonry only six weeks before the introduction of the new temple rituals, which “mirrored Masonry partly in form, particularly in the use of certain signs and grips, and in its construction of an initiation rite through elaboration of Biblical story and drama . . . Freemasonry offered the same sense of an ordered world that Joseph was seeking to find in his faith” (p. 77). Joseph’s willingness to use Masonic rituals to advance what Bowman calls “radical theological innovations” (p. 78) is consistent with Aristotle’s definition of rhetoric, that one should both find and use the means of persuasion available that are most appropriate for the occasion.

When the Nauvoo endowment was finally implemented, Samuel Brown (2012) notes that “Joseph Smith employed the story of cosmic origins he had been elaborating for years without Masonry. The secret codes of Masonry mimicked the pure Adamic language; the Mormon pantheon supplied the truly omnific word. The connections to Adam that the [endowment] amplified both personalized the Fall and situated life on a cosmic scale” (p. 185). The endowment was created, at least in part, for the purpose of empowering would-be missionaries with the knowledge necessary for them to share the gospel in a meaningful way. The washings and anointings that occurred in the Kirtland endowment would enable elders to be “perfected in their ministry for the salvation of Zion” to “[convince] the nations . . . of the gospel of their salvation” (D&C 90:8,10). The end goal, at least for many recipients of the Kirtland ordinances, was to become a better rhetor like earlier missionaries, crying repentance, contending against no one but the devil, and “speak[ing] the truth in soberness” (D&C 18:14, 20-21).

By dramatizing scriptural accounts of the Creation and Fall, Mormons – to paraphrase Samuel Brown (2012) – “[return] to the beginning . . . [to] see the glorious ending” (p. 185). The endowment reinforces the role of inherent human weaknesses and the importance of faith and obedience by recreating elements of the Biblical story of Adam and Eve. Participants take on the dramatized roles of these two characters respectively, the men imagining themselves as Adam, the women taking on the role of Eve. This is designed to illustrate the Plan of Salvation. In order to clearly understand the story of the first man and woman and their relationship to God, Mormons must essentially become those individuals, communicating with and experiencing Deity in the pattern their earliest ancestors had been divinely instructed to follow.

The story of the temptation of Adam and Eve serves to illustrate underlying rhetorical themes in the endowment itself. Having been placed on earth as innocent beings, knowing neither good nor evil, both individuals are commanded not to partake of the forbidden fruit. Later, as Lucifer approaches Eve, she immediately questions his intentions. She recognizes the Great Deceiver’s persuasive strategy to prompt her to disobey God. The account of the Fall in the endowment is slightly different from scriptural accounts in Genesis and Moses. Both of these accounts state that Lucifer told Eve that she wouldn’t die by partaking of the fruit (Gen. 3:4 KJV; Moses 4:10). However, Eve is never told this lie in the temple drama.

As in the scriptural accounts, Eve is promised that her eyes would be opened, that she would be like the gods, knowing good from evil (Gen. 3:5 KJV; Moses 4:11). Only Adam is told the lie that he would never die. Adam of course, isn’t deceived by Lucifer’s falsehood. It is only after he is persuaded by Eve, not Lucifer, that Adam agrees to partake of the fruit. Unlike traditional accounts that characterize Eve as a deceiver, and which were used to oppress the role of women in faiths around the globe, Eve never lies to Adam in the temple drama. She fully acknowledges the consequences of the transgression and appeals to transcendence as her persuasive strategy. Both individuals recognize that the order to multiply and replenish the earth superseded the commandment that they not partake of the forbidden fruit. Their eyes are thus opened to a new world, knowing good and evil. They see as the gods.

By recreating the nuances within the scriptural account, participants are prompted to both understand the story being portrayed and empathize with the characters in the original story. This, in turn, allows for the creation other nuances and even facilitates the emergence of paradoxical ideas about man’s relationship to God. It could, for example, shed light on how the endowment can reinforce one’s view of human inadequacy, and at the same time enhance one’s view of a divine birthright and potential for growth in the eternities. These realizations, and others unmentioned, occur through the interpersonal transmission of symbolic, persuasive messages.

Because rhetoric can be used to examine multiple worlds, the social, the scientific, the artistic, and the philosophical, “the realm of rhetoric is powerful” (Hart & Daughton, 2005, p. 11). The nature of rhetoric itself allows for a great deal of flexibility, embracing a wide variety of fields to explore the ways we influence one another through the exchange of ideas. As I’ve demonstrated here, religion, and more specifically Mormon Studies, provides rhetorical critics a literal treasure trove of possibilities. Rhetoric enhances and reframes the way we interpret and define our faith and what these rituals mean to us. As Hart and Daughton (2005) argue, rhetoric “operates like a kind of intellectual algebra, asking us to equate things we had never before considered equitable” (p. 16). They further note that for “religions to thrive, there must be apostles . . . To turn our backs on rhetoric would be to turn our backs on the sharing of ideas and hence any practical notion of human community. So rhetoric is with us because it must be with us” (p. 19).

By exploring the message of the endowment, both in its spoken and nonverbal forms, participants can attempt to interpret the “intricacies and functions of language patterns . . . clearly displayed in performance” (Frey, Botan & Kreps, 2005, p. 252). As mentioned before, I believe rhetoric is a neutral tool that is neither inherently good nor inherently bad. When properly applied, it enlarges our view of the world, unburdens us by facilitating expression, and empowers us by providing multiple methods for understanding. Through the mystical rhetoric of the endowment, Latter-day Saints can, like Thomas in the New Testament, join a close-knit community of rhetors who “bear witness of the Light, that all men through [them] might believe” (John 1:7 KJV). Thank you.

[1] It is worth mentioning here that Skinner is, whether intentionally or not, joining both Strong’s and Thayer’s entries for the term. Thayer translates it as “to show or prove by sure signs” while Strong addresses the derivative tekmar as meaning “a token.” See reference number 5039 in both publications. My thanks to Brad Kramer, who led the session, for prompting this clarification.

References

Aristotle. (2011). Rhetoric. Los Angeles: Indo-European Publishing.

Bowman, M. (2011). The Mormon People: The Making of an American Faith. New York: Random House.

Brown, S. (2012). In Heaven as it is on Earth: Joseph Smith and the Early Mormon Conquest of Death. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dues, M., & Brown, M. (2004). Boxing Plato’s Shadow: An Introduction to the Study of Human Communication (3rd ed.) New York: McGraw-Hill.

Frey, L. R., Botan, C. H., & Kreps, G. L. (2000). Investigating Communication: An Introduction to Research Methods (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Hart, R., & Daughton, S. (2005). Modern Rhetorical Criticism: Third Edition. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Nibley, H. (1956). Victoriosa loquacitas: The rise of rhetoric and the decline of everything else. Western Speech, 20, 57-82.

Skinner, A. (2010). The Dead Sea Scrolls and the world of Jesus. Studies in the Bible and Antiquity (Vol. 2). Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship.

Petersen, B. (2002). Hugh Nibley: A Consecrated Life. Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books.