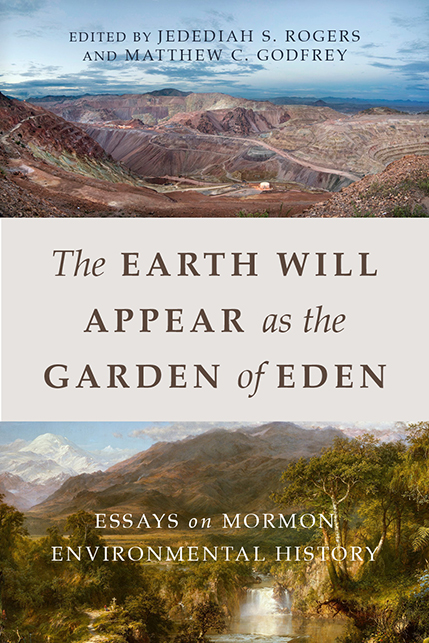

Review of Jedediah S. Rogers and Matthew C. Godfrey, The Earth Will Appear as the Garden of Eden: Essays on Mormon Environmental History (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2019).

“Mormon environmental history” may sound like an odd or arcane topic, but it turns out to be a central and fruitful one. Even leaving aside the political footballs of climate change and pollution of air and water, environmental issues arise in Mormon history time and time again.

Consider, for instance, the pride that Mormons take in having made the desert blossom as the rose. Or consider the food shortages that both settlers and Native Americans faced when thousands of Mormon pioneers streamed into the Salt Lake Valley with few resources and grazed their animals on the indigenous plants. Consider the “miracle of the seagulls,” in which swarms of crickets (actually locusts) threatened to devour settlers’ crops until flocks of seagulls descended and ate them. Or consider Ammon Bundy and his sense of entitlement to graze cattle on federal land.

If you’re suddenly wondering how you’ve missed this important topic, have no fear. For a crash course in Mormon environmental history, just pick up Jed Rogers’ and Matthew Godfrey’s collection of essays, The Earth Will Appear as the Garden of Eden: Essays on Mormon Environmental History.

Rogers and Godfrey kick off the volume with an introductory essay that sets the tone. The volume focuses on the questions of how religion has shaped the environment and what the environment has meant to religious people. The editors express a wish to avoid narratives of “declension,” which portray religion as having fallen away from some original ideal relationship with nature, and to focus on more nuanced sorts of storytelling. They also critique scholars who portray Mormons as categorically the bad guys, wreaking environmental havoc out of ideological stubbornness or willful spite.

In this collection there is not a single weak essay, though the authors don’t always live up to the editors’ desire to avoid “declensionist” thought. Essays by Sara Dant and Thomas G. Alexander narrate Mormon history in this mode. Both authors provide examples of “salutary environmental theology” promoted by Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, and blame a sort of sinful fall into secular capitalism for that theology’s decline.

Both Dant’s and Alexander’s essays are richly researched and provide important historical timelines of environmental damage and environmental legislation that cannot be skipped. However, both also make strained connections between early Mormon environmental theology and early Mormon communal economics, and both exaggerate Mormon communalism while eliding the capitalist aspects of early Mormon thought. Alexander commits the further error of villainizing the “secular,” and even of blaming apostates “like the Walker brothers during the late 1850s and the Godbeites during the late 1860s and early 1870s” for having somehow “sidetracked [Mormon] teachings about the sanctity of all life and environmental protection” (58).

The rest of the volume’s essays live up better to the editors’ ideal.

For instance, Brett Dowdle pens a fascinating treatment of how Mormon missionaries in Britain disdained its urban poverty and pollution and sought to resettle the poor as farmers in Nauvoo. Many converts who took them up on this, however, found Nauvoo a swampy backwater and themselves unprepared for agricultural life.

Betsey Gaines Quammen narrates the creation of Zion National Park, illustrating how the park’s creators physically displaced both white residents and indigenous Paiutes in order to make room for the park, and then erased the memory of Paiute inhabitation by replacing Paiute place names with names of white Christian origin.

In one of the volume’s more important essays, Jeff Nichols reminds us that although historians think of Mormons as a farming people, they were at least as much livestock-raisers as farmers. He documents the overgrazing of Utah’s fragile arid grasslands by enormous herds of sheep and cattle, causing environmental damage as early as 1849. By the 1860s and 1870s, overgrazing had devastated indigenous plants and destabilized mountain watersheds, causing devastating flash floods. The essay also documents how access to grazing lands became a source of economic inequality in Utah, and how Native Americans were displaced by Mormons’ livestock nearly as much as by Mormons themselves.

Another important essay, by Brian Frehner, documents just how big a problem the flash floods actually were. “Environmental factors,” especially flash floods, “resulted in the failure of forty-three communities”—a full 8% of the 543 communities Mormons founded in the nineteenth century (185). Residents of Woodruff, Utah built 13 dams in 40 years, and 11 of them washed away (189). Clark County, Nevada saw 169 floods in the 70 years from 1905 to 1975, damaging bridges, railroads, homes, farmland, and irrigation canals (191). In fact, flash floods still occur along the Virgin River today, including a 2015 flood that killed 20 people.

As Frehner points out, the settlers’ failure to fully tame Southern Utah’s rivers problematizes their view of themselves as model irrigators. Likewise, Brian Cannon documents how over-irrigation of submarginal farmland in the late nineteenth century actually damaged topsoils and produced poverty-level yields for farmers. Cannon shows that the agrarian ideal to make every man a farmer proved unsustainable, and Mormons moved en masse to cities in the twentieth century. A subsequent essay by Nathan N. Waite illustrates how late-twentieth-century Mormons replaced their agricultural ideal with a love of gardening.

One of the more interesting themes running through the book was the concept of “desert.” Mormons consider themselves to have made the “desert blossom as a rose,” principally through irrigation. Several essays challenge this idea, however. When pioneers first arrived in the Salt Lake Valley, they found lush meadows and large amounts of fresh water. Only after overgrazing destroyed the native plants and invasive species like sagebrush and Russian thistle displaced them did the landscape become more desert-like. The idea that the pioneers had settled in a desert was largely a later creation, as their memories of their first impressions were colored by the landscape they now saw. As Jeff Nichols argues, “Rather than redeem a desert, they had helped create one” (168).

There’s plenty more of interest here, including important discussions of Mormon concepts of land and of Mormon attitudes toward economic inequality. It would be redundant for me to rehearse them all here, because of course you’re all going to go read the book. For the more theologically inclined, the book concludes with an essay by General Authority Marcus B. Nash laying out the scriptural foundations of a Mormon environmental theology. With any luck, this book will not only educate Mormons about environmental history, but also stimulate them to become better stewards.