“Thunder From the Right: Ezra Taft Benson in Mormonism and Politics” – Edited by Matthew L Harris

Published by: University of Illinois Press, 2019

Number of Pages: 247, Paper Binding and eBook, Cloth by Special order

Price: Paperback: $27.95, eBook: $14.95, Hardback: $99.00

I teach college English. A big part of my job is teaching freshman to avoid using clichés and buzz words in their essays. I promised myself I’d be a good boy, but I’m going to give in to temptation. “Thunder From the Right” is an outstanding book by an excellent group of scholars who have written a collection of essays that will amaze, fascinate, inform and probably trouble you.

I’ll be honest, I went into “Thunder From the Right” skeptical that I would learn much from it. I’ve long had a fascination with Ezra Taft Benson because of the particular way that he influenced my life. Benson bookended my teenage years: I was 12 when he became president of the LDS Church and he passed away a couple of months before I returned from my mission. On top of that I grew up in a family of Utah Democrats: my parents, my parents-parents, and their parents back to Utah’s statehood were proud Democrats. Benson did not like Democrats and infamously said that good Mormons could not be good Democrats. Take hearing about Benson and his teachings constantly during my formative years, add two years of knocking on doors in Oklahoma testifying to strangers that Benson was a prophet of God, and mix in that Benson said that my family did not even deserve to be Mormons and you get a man who I had complicated feelings about. This led me to read any material on Benson that I could get my hands on. I thought that I had learned it all. “Thunder from the Right” proved me wrong; its compact 238 pages of text taught me a wealth of information on Benson and gave me a greater understanding of his personality and motivations for his beliefs and actions.

“Thunder” is a collection of eight essays edited by Colorado State professor Matthew L. Harris. The contributors are all names that you will know if you ready scholarly Mormon history: Brian Q. Cannon, Gary James Bergera, Robert A. Goldberg, Newell G. Bringhurst, Matthew Bowman, Andrea G. Radke-Moss, and J. B. Haws. Harris sets up “Thunder” with a brief ten-page introduction that, much like a good movie trailer, whets the appetite, sets high expectations, and gives you just enough information to lure you in and make you feel that what is to come is going to be irresistible. He concludes by stating his hope that “Thunder” will:

“offer a fresh and stimulating retrospective assessment of Ezra Taft Benson’s life and legacy, particularly his considerable accomplishments as a public servant, Cold War figure, and religious leader in the half century after World War II” (p. 10).

Ezra Taft Benson on the cover of Time Magazine, April 13, 1953

I can say that the book meets those expectations. As this is a collection of work by eight authors, I will provide a mini-review of each essay. “Thunder” is divided into two thematic parts. Part One, which is made up of the first seven essays, is called “Politics and Cold War Anxieties.” This is an excellent description for this section as readers will be intimately familiar with Benson’s anxieties and fears by the time they finish this section of the book.

Ezra Taft Benson inspects a farm during a drought, date unknown

Brian Q. Cannon, professor of history and director of the Charles Redd Center at BYU, leads off with the essay “Ezra Taft Benson and the Family Farm.” Before leaving for Washington DC to take up his post as Secretary of Agriculture, Benson received a blessing from David O. McKay who said “as an apostle of the Lord Jesus Christ [y]ou are entitled to … divine guidance which others may not have.” He also “blessed him to discern ‘the enemies who would thwart the freedoms of the individual as vouchsafed in the constitution’ and to ‘be fearless in the condemnation of those subversive influences, and strong in your defense of the rights and privileges of the constitution’” (p. 28, brackets and ellipses in the book). Cannon then deftly outlines how Benson took this as a mandate that he was on a “divine errand” (p. 36) to fight his perceptions of socialism in farming and the government and impose his own version of Mormon ideals through official policy.

Nikita S. Khrushchev pats “Alice” during a visit to the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) Center in Maryland September 16, 1959. Ezra Taft Benson and U. S. Ambassador to the United Nations Henry Cabot Lodge look on. Photo courtesy of National Archives

Gary James Bergera, managing director of the Smith-Pettit Foundation, takes on and debunks one of Benson’s most famous stories in “Ezra Taft Benson Meets Nikita Khrushchev, 1959: Memory Embellished.” Growing up at the tail end of the cold war, and as a teenager during Benson’s years as LDS Church president, I cannot tell you how many times I heard the story of how Benson, as Secretary of Agriculture and with the authority of the apostleship to give him strength, stood up to and defied the “evil” Nikita Khrushchev, leader of the Soviet Union. The way the story was retold, Benson came out as something of a patriotic capitalist Mormon superhero. Bergera documents that Benson and Khrushchev did indeed meet briefly in 1959 and then proceeds to explain that when Benson told the story to a BYU audience seven years later he “recast the meeting as a near-mythic confrontation between good and evil” (p. 53). Bergera then outlines why he thinks that Benson did this and then shows how the story grew with each retelling over the years by Benson. Bergera even proves that the most famous quote that Benson attributed to Khrushchev from the meeting that “your grandchildren will live under communism,” to which Benson was supposed to have heroically defied/prophesied “Mr. Chairman, if I have my way, your grandchildren and everyone’s grandchildren, will live under freedom” (p. 55) likely was NOT even said to Benson. In fact, Benson probably borrowed this Khrushchev quote from someone else’s experience! Bergera has crafted a compelling essay on memory and motive.

Robert A. Goldberg, professor of history and director of the Tanner Humanities Center at the University of Utah, contributes the essay “From New Deal to New Right.” Goldberg makes the contention that “in the late 1950s the power of American conservatism appeared spent”, that Eisenhower had no plans to “roll back, New Deal and Fair Deal reforms” started by FDR, and that outside of the “mainstream, conservatives had fractured into loosely structured ideological camps.” He also states that for Mormons of the time to “connect with all of these (conservative) camps” they would need “a Moses to lead them” (p. 71). Goldberg writes that Benson had the “timing, opportunity, and desire … to play the role” and that Benson “burned with ambition to lead America and his church past tribulation” (p. 72). Goldberg then shows with excellent documentation how Benson from the early 60’s to the early ’80s, through nearly every speech and action, including his involvement in the John Birch Society, sought to guide Mormons to his political promised land and in so doing pretty much created modern Mormon conservatism.

Governor George Wallace. When Wallace ran for president in 1968, Benson wanted to be his running mate. Benson told John Birch founder Robert Welch about Wallace “He’s a great guy. We have a lot in common”

Newell G. Bringhurst, emeritus professor of history and political science and author of 13 books, authored an essay titled “Potomac Fever: Continuing Quest for the U.S. Presidency.” I won’t say much about this essay other than it is a remarkable piece of scholarship and writing that shows that Benson really, really, REALLY, REALLY wanted to be president of the United States very, very badly and that he was willing to cuddle up to some nasty racists to get there.

Matthew Harris, along with his editing duties, penned the essay “Martin Luther King, Civil Rights, and Perceptions of a Communist Conspiracy.” You probably knew that Benson was influenced by Herbert Hoover, that he was convinced by Robert Welch that communist conspiracies were everywhere, that he loved the John Birch society, that Welch even convinced Benson that his old boss former president Eisenhower was a tool of the communists, and that he hated Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights movement and was convinced that they were being used to turn the USA over to the communists. I knew of these things, but I had no idea how severely Benson was into these ideas and conspiracy theories until I read this essay. It is a must read. It blew me away. I couldn’t put it down. I’m going to buy Harris’s next book just based on this essay. It is definitely a you won’t believe it until you read it type essay but you will believe it because it is so well written.

Matthew Bowman, associate professor of history at Henderson State University, starts off the second section of the book, “Theology,” with the essay “The Cold War and the Invention of Free Agency.” Bowman begins his essay by describing teachings about the agency of man during the Second Great Awakening and the teachings of Joseph Smith, Brigham Young and other early LDS leaders on the topic. He explains that the free agency taught by these early LDS leaders and others such as Talmage and Joseph F. Smith was strictly tide to producerism, that “Free agency was centered on one’s individual choices, and Mormons like (Joseph F.) Smith expected to exercise it regardless of pressures, needs, or external forces” (p. 162). Bowman then goes on to prove over the course of his essay that, during his time in the LDS hierarchy, Benson completely transformed the LDS idea of what agency was. He shows how this transformation began in the 1940s and 50s when Benson “laid the groundwork for a transformation of free agency from something sustained through moral exertion into something that stood eternally in peril” (p. 165) and then documents how Benson, with the help of Mormons like W. Cleon Skousen, “reinterpret(ed) free agency in a way that bound Mormon theology to libertarian politics” (p. 168). He also explains that Benson reinterpreted the Mormon concept of “the War in Heaven” to be “a political allegory in the Cold War” (p. 171). Its an amazing essay and Bowman makes a compelling case in showing that Benson completely redefined an LDS doctrine to suit his personal beliefs and ideals.

Every essay in “Thunder” is excellent. I encourage the careful reading of each and every one. But if I was going to name a favorite, if I were to say to someone, “if you are only going to read one essay in this book and no more read this one,” it would be “Women and Gender” by Andrea G. Radke-Moss, professor of history at Brigham Young Idaho. I’ll be completely frank, Moss’s essay is troubling and frustrating to read, but you will be well compensated for having done so because it is brilliant, compelling, and well, fantastic. Benson loved his wife Flora deeply and was fiercely devoted to and protective of her and she felt the same way about him. But Benson held some extreme ideas about women and what he saw as their divine role as wives and mothers. Over his nearly 50 years in the LDS hierarchy, he has a lot to say about women, some of which many would see as troubling, including blaming women and their behaviors for many of the ills of modern society. This was a hard but important essay to read. Moss’s skill as a writer and her passion for the subject make this an especially compelling essay.

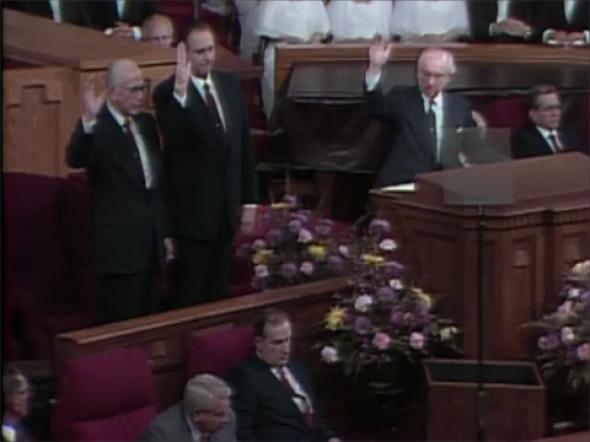

J. B. Haws, assistant professor of church history and doctrine at BYU, wraps “Thunder” up nicely with his essay about Benson’s “LDS Church Presidency Years, 1985-1994.” It’s a fantastic essay that describes the juxtaposition of Apostolic Benson, the world that he lived in and his ideas, with the evolving world and LDS Church of the 80’s and 90’s and shows how the Benson that I experienced as a youth tied to the Benson from the rest of the book.

If you are interested in the development and course of twentieth century Mormonism, if you want to understand the creation and development of modern Mormon political conservatism, if you want to have an understanding of just who Ezra Taft Benson was and why he was who he was, then read this book. It’s short, it’s engrossing, it’s important, and it will give you a greater understanding, not only of Benson, but of modern Mormonism as well.