A preliminary note on audience: I’m new to the blog as a writer, but I’ve been reading since Chris started it all so I realize we’re not all Mormons here. I assume a Mormon audience in this post because it seemed fitting for the review. I’m hoping it’s useful to give Mormons and non-Mormons alike a sense of how the faith feels to me from the inside right now. (But really, I’m just trying to preach to Chris.)

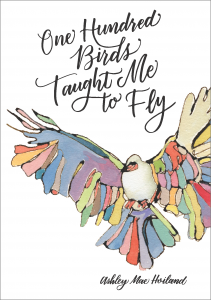

Ashley Mae Hoiland’s new book One Hundred Birds Taught Me to Fly is the newest installment in the Maxwell Institute’s Living Faith Series. I was a big fan of the series already, and Ashmae’s book only improved it. Like the other books, it ably reveals how familiar parts of Mormon faith and practice shine with a light we have forgotten or perhaps overlooked.

But One Hundred Birds also stands out in some really significant ways.

The distinguishing characteristic of the book is its femininity. I’m told One Hundred Birds is the first Maxwell Institute monograph* by a woman (a reason for both rejoicing and repentance), but it’s not merely the bare fact of a woman’s voice in the series, or the conversations the series takes part in, that is notable. And it’s not just the presence of a woman’s stories either. (The storytelling of Sam Brown’s First Principles and Ordinances drew almost exclusively from the Mormon Women Project.) It’s the feminine content of the book that adds exciting substance to our conversations about the conditions and possibilities of contemporary Mormonism.

Ashmae’s interest in embodiment may be the most striking example of this. It grows out of her attraction to Mormon belief in a Heavenly Mother, but explorations of a divine feminine are shaped differently when they are led by Terryl Givens or Taylor Petrey. Ashmae is more interested in experiencing embodiment than she is examining the historical manifestations or intellectual possibilities of Mormon doctrine concerning gender. To crib from Nibley, she wants revelation, not theology.

This perspective catalyzed memory for me in a way that allowed me to more fully experience moments of my own sacred history, and this felt so very Mormon to me. Not only because I felt the materiality of my body and creation to be an indescribable good, but also because I felt how this gift is inextricably linked to history itself, which is as essential to Zion as economic equality. God gives us a body, a family, a world, but he also gives us a story to remember, to mourn, to celebrate.

This vision of history was especially present in Ashmae’s tender storytelling, which gives careful shape to a personal, interior world of worry and wonder, waiting and waking. But rather than merely outline the contours of the life of Ashley Mae Hoiland, the book’s stories place in our hands a thick weave of connections between a dazzling universe and a small but powerful Mormon tradition and community. Ashmae invites us to feel the subtle textures of this quilt by showing how familiar features of Mormon life offer—and are meant to offer—a vision of life that is about so much more than Mormonism.

Adam Miller’s Future Mormon, a General Conference talk by Elder Uchtdorf, or a host of other contemporary resources may address members of the church who are disillusioned, who harbor heartache about institutional boundaries (old and new), or who thirst for answers to questions about history, sex, or some other thorny subject. But like nothing I’ve yet encountered, One Hundred Birds offers this same demographic an occasion for inhabiting creation, bodies, and history in a way that speaks to needs we might have forgotten we have in our anxious analyzing of the moment. It gets us out of our minds and into the mysterious matter of our Mormon souls.

The book is not primarily concerned with addressing the issue of disaffection and disillusionment among critically minded members of the contemporary church, as the series’ recent installments have been. It speaks to the situation, but doesn’t aim at it. Earlier books in the series have done the same, but when Hoiland addresses the issue, she does it in personal terms unlike anything presented in them. Her primary interest is how to live, not how to think, so she explores ideas as part of (rather than separate from) experience.

This is not to say that ideas are irrelevant or peripheral for her. The book makes clear Hoiland’s deep concern about the life of the mind. But throughout her intellectual wanderings, she remains persistently aware that her mind is part of her body, which is itself a part of a vast and strange and pulsing universe.

For example, in the book’s sections about her mission to Uruguay, Ashmae illustrates how young elders and sisters often learn to embed themselves in the tangible, mundane particulars of a place in a way few outsiders can. She shows how Mormon mission life acquaints its participants with both the voiceless wounds and unexpected inspirations hidden in the complex inner worlds of strangers. As I envisioned a young Ashmae bringing a community together through a quietly courageous community art project, I was awestruck by the way Mormon mission life and theology can direct the action and attention of young, inexperienced twenty-somethings, how it can make them witnesses of the astonishing grace that appears in people and places that seem to be ignored and forgotten by the world and by God.

The book also shares many scenes from Ashmae’s post-mission life in the “mission field,” but I sometimes found myself conflating times and places. This was partly because the book is arranged in non-chronological bursts, but there was also the fact that I felt a deep connection to the way revelation seemed to embed itself in the rocks of her service in Uruguay and slowly morph into the strange but radiant gems of her life as a young mother in Europe. Of course, some of these rocks crumbled completely, but many of them took new form, despite breaking under the weight of an ever-expanding world.[1] This touched me deeply because it helped me appreciate anew how this same transformation has occurred in my own life.

I realize, of course, that not all Mormons have found such abiding, renewing vitality in their mission experience. (I know few whose experience was more positive than my own.) But I think one of the important gifts of my own missionary service is on offer in the ward life known by most practicing Mormons. At entirely unpredictable times in the work of numerous callings I’ve had since my mission (and most especially as a home teacher), I’ve been stunned with the way God’s work radically transcends our understanding of it. As I’ve gone out to meet people, to form new relationships, to offer testimony of God’s goodness, I’ve learned that God has already been at work in quiet and unassuming places and that, like Mormonism itself, LDS missionaries haven’t started the work (God forbid!), but have been sent into the world to imperfectly add to and inadequately participate in what is already underway.

In what I found to be its most important parts, Ashmae suggests how this same revelation might be found in the temple, which she embraces in both its pain and its promise. I sense that this wide embrace is just what many of my fellow saints need when it comes to discourse about the temple. Ashmae exemplifies how we can’t honestly honor either the heartache or the holiness without recognizing the blurriness of the lines we try to draw between the personal and the communal, between scattering and gathering, between the lost and the found.

In the book’s most poignant paragraph for me, Ashmae takes up the experience of a temple sealing without certain family members, an experience much more common than much Mormon celebration of the temple acknowledges. Speaking of her sister’s sealing, she writes: “I held back tears as I looked into that mirror and did not see the reflections of two of my siblings next to me. . . . My brother and sister were watching my children downstairs in the small waiting room. My pain had nothing to do with the reasons they were not there, just simply that they were not.” The temple marks, even creates, a separation. Ashmae does not push this uncomfortable fact under the alter, and instead sees the resulting pain and distance as part of a picture framed by the temple’s hopeful promise, its cosmic drama.

This and other scenes from the temple echo the boldness of early Mormon temple culture as they articulate a vision of God’s work as exploding beyond the concerns of the nuclear family. Temple ordinances are for the human family, not merely our own, and those same ordinances are for the living as much as the dead because they are an unqualified testimony to God’s commitment to life, despite its terrors. Death is conquered by a divine love, doubly offered by a Male and a Female, that will never cease its work of breathing new life into our collective story, which is itself an essential part of the Zion it brings us together to build. We join hands and find Christ in our clasps, with a reminder that the scars of our story can be redeemed.

Or as Ashmae describes her own sealing, “In some way, in the temple that day, the borders of loss and reunion blurred. . . . Later that day, at the wedding lunch, we stood in turn and shared a favorite memory, and many of us cried out pure joy and celebration. Maybe then, if I had spent more time in the temple that day looking carefully into those mirrors, I would not have seen absences, but the figures of all those memories and stories that make up our lives. I may not have seen my siblings standing next to me in the present, momentary frame, but they would have surrounded us both a thousand frames backward and forward–their absence in that room was not hopeless for me.”[2]

We get a taste for the love that is behind this hope in the glimpses we get of Ashmae’s passionate and perceptive mothering, which are all over the book. They uncover a world of childhood that, as Ashmae reminds us, Christ calls us to recover. “As an adult I’ve often interpreted Christ’s instruction to become like a child as a call to meekness, humility, submissiveness,” she writes. “But this childhood world where I see my own children thrive is colorful, textured, a little unruly, unpredictable. . . . My children have taught me to play again. . . . They play by moving their thoughts around, rearranging the world one hundred times in a day; they play by asking questions without guilt or embarrassment.”

Ashmae describes the fear that came with her gradual realization that Mormon faith demands that she take the risks of adventure and experimentation. But along with the disconcerting departure of “the talkative God” she seemed to know so well in her youth came an “uprising of the godly” that has whispered its way into her faith’s new form. “Steps that I originally thought were headed away from God and away from my spiritual self [] were in fact paths that unexpectedly led me nearer to him. . . . There is a time to run home, back to the familiar, back to the safety of all that is known, but there is also a time to untether your heart and let it go, even far, in search of the God you want to know.”

I couldn’t help but think of a Mormon Eve when I read that passage. Although she doesn’t figure prominently in the book, Eve seems to hover around its stories, encouraging Mormons to trust that Heavenly Parents are ready, willing, and able to make use of earnest but imperfect choices. In the absence of a talkative God, we feel alone, like Eve in Eden, and are left with no choice but to act in faith, to take a risk, to become an agent. If One Hundred Birds has a message, I think that’s it.

The way Eve haunts the book captures me because I suspect we, Mormon men especially, have a thing or two to learn from her. But it also grips me because it reminds me of Christ’s subtle presence in the temple, which we might see as a model for work in his kingdom. Presence in public spaces matters, but any everlasting work draws on a spirit that moves fearlessly below the surface of things.

With One Hundred Birds, Ashmae points us to that spirit. Her book is like a quiet Mormon ward building in a small town of a forgotten country. The chapel isn’t remarkable for its style or beauty. It’s simple and clean, apart from fresh children’s snacks that lie crushed under a back pew, and it feels inviting, like the modest home of a friend. But when its plain windows open, they let in a light that reveals a radiant kingdom, unassuming in its unimagined power, a kingdom not of this world.

At the end of an election season in which we are tempted to look to the powers of this world for promises of salvation, I found this to be both a challenging and comforting message.

___________________________________________________________________

[1] I’m stealing this metaphor straight from Ashmae, whose husband is a geologist. After discussing her disillusionment with the term “faith crisis,” she writes, “Since then, my eclogite-like crisis has moved deeper and deeper into the molten, mysterious mantle of my heart. It has been heated to extraordinary temperatures, changing its properties and molding into something entirely different. I am not sure exactly when or how it will resurface, but I eagerly wait for that moment, perhaps far off, when I will see it in some other dreamlike landscape. I will run my fingers over it in amazement because it will sparkle in a way I could not have predicted, in a way it did not before. It will no longer be my crisis, but rather my story . . .”

[2]”I wanted my siblings to know,” Ashmae adds, “that while the present moment in the temple mattered immensely, and it was beautiful, that the thousands of moments before—when my sister helped my marrying sister to do her hair that morning, the time we spent at our kitchen table together, the hour we spent in the temple two decades prior being sealed as a family, and then the thousands of hours that will still come as we continue to grow up together—those moments matter. . . . Those many vibrant hours are what I saw in the temple mirrors that day. I want to tell my brother and sister that I saw them there, that when I looked into the mirrors I was not alone at all, that I saw us all going behind me and in front of me together for as far as I could see.”

* When I first posted this review, I used the word “publication” when I should have said “monograph.” Thanks to Blair Hodges for pointing this out. The Maxwell Institute has published articles by women and books that have had woman editors, some of which I’ve had the pleasure of reading. But Ashmae’s is the first MI monograph.