Content warning: This post discusses the dramatic portion of the early temple endowment.

In an 1863 letter to Brigham Young, the great Mormon hymn-writer W. W. Phelps enumerated the callings he had received from Joseph Smith. One in particular stands out. “My sixth office, As King’s Jester and Devil,” he wrote, “I have performed as well as I could for twenty years. Hope to do better when more spirit comes.”[1]

At least one historian dismisses this remark as a symptom of dementia. But in fact Phelps wasn’t out of his mind when he wrote this—at least, no more than usual. The eccentric author of “If You Hie to Kolob” had always been a little crazy, to Mormonism’s great enrichment. His expansive mind pushed the boundaries of Mormon thought into territory both brilliant and bizarre.

But Phelps’s “sixth office” was no delusion of a demented mind. It was a very real calling that he took quite seriously: his comic role as Satan in the temple drama.[2] It was a “jester’s” role perhaps because, as Martin Luther once said, “The best way to drive out the devil, if he will not go for texts of Scripture, is to jeer and flout him, for he cannot bear scorn.”[3]

Anyone else might have resented such a calling, but Phelps was strange and devout enough to treasure it. Once in 1853 Brigham Young mentioned the devil from the Tabernacle pulpit. Phelps called out from his seat in the stand, “We could not do very well without a devil.” “No, sir,” Brigham replied, “you are quite aware of that; you know we could not do without him. If there had been no devil to tempt Eve, she never would have got her eyes opened. We need a devil to stir up the wicked on the earth to purify the Saints.”[4]

Many temple initiates of the 1850s and ’60s remarked on Phelps’s enthusiastic performances of the Satan role. Their commentaries reveal Phelps as a great comic actor and the endowment as a lively drama with costumes, sets, and props.

One of the earliest accounts comes from an exposé published by apostate Mormons Increase and Maria Van Dusen in 1847. The Van Dusens had been endowed the previous year at Nauvoo on January 29, 1846. They identified Orson Hyde as the actor who played the devil on this occasion, but may have misremembered, because the performance sounds like Phelps.

Whoever the actor was, his “part was well sustained, he being two thirds devil himself.” The serpent “comes into the garden in caricature costume, and disturbs the quiet abode of the man and woman,” the Van Dusens reported. “After Orson receives the curse from Brigham [in the role of God], he gets down on his belly and crawls round on the floor a few times, and finally drags himself out of the room.”[5]

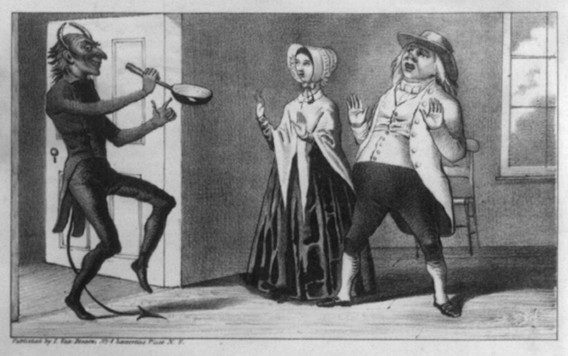

The most delightful thing about the Van Dusen exposé is that they illustrated the drama in an eight-panel lithograph foldout. The illustrations are surely more artist’s conceptions than realistic portrayals, but they capture something of the energy of this costume drama. This devil cuts a perfidious figure in his grinning horned mask, his long pointed tail, and tailcoat suit. He leers at a scantily clad Eve from behind the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. He tries to lure her astray with his sinful fiddle music.

The most remarked-upon aspect of Phelps’s performance was his habit of crawling or wriggling on the floor. Two years after the Van Dusen exposé, the New York Times published a colorful biopic on “King’s jester” Phelps—“a great man in Mormondom” who in the paper’s opinion had “too many screws loose.” In the endowment, the paper reported, “he plays the part of the serpent-devil” and “wriggles and hisses so much like a snake, that he is regarded by all the Saints as indispensable.”[6]

John Hyde Jr., endowed in February 1854, found Phelps’s performance so shocking that he punctuated it with parenthetical exclamation points. “Some raisins were hanging on one shrub,” Hyde wrote, “and W. W. Phelps, in the character of the devil, which he plays admirably (!), endeavored to entice us to eat of them. Of course, ‘the woman tempted me and I did eat.’ We were then cursed by Eloheim, who came to see us: the devil was driven out, and this erudite astronomer and Apostle (!) wriggled, squealed, and crept away on his hands and knees.”[7] Fanny Stenhouse, endowed in 1855, likewise saw Phelps “upon his hands and knees, making a hissing noise as one might suppose a serpent would do.”[8]

Phelps’s use of costume in the drama is also well attested. “There is an eccentric Mormon at Salt Lake City of the name of W. W. Phelps,” wrote Artemus Ward. “It is said he enacts the character of the Devil, with a pea-green tail, in the Mormon initiation ceremonies.”[9] The Van Dusens’ reference to “caricature costume” has already been quoted.

A more detailed description of Phelps’s devil motley appeared in Ann Eliza Young’s account of her 1860 endowment. “Satan was dressed in a tight-fitting suit of black, slashed with pink, pointed shoes, helmet, and a hideous mask,” Young wrote. “His costume, with the exception of the mask, resembled very closely the dress always worn by the stage Mephistopheles. I think he must have had different costumes, since it has been described several times, and the descriptions have varied in every case.” Illustrator Stanley Fox rendered this costume in several delightful vignettes for Young’s book.

Young also vividly described the setting in which Phelps played his character. The tree of life was represented by “a small evergreen” with raisins tied to its branches. The Garden of Eden was depicted by “painted scenery and furnishings.” Into this setting “Satan entered and commenced a desperate flirtation with the coy and guileless Eve,” played by Eliza Snow. Phelps proffered the fruit, and Eliza Snow ate it. “The devil was then cursed, and he fell upon his hands and knees, and wriggled and hissed in as snake-like a manner as possible.” At sixty-eight years old, Phelps still played his part with the spry enthusiasm of a much younger actor.

“It requires some imagination to invest this place with all the beauty that is supposed to have belonged to the original garden,” Young complained of the ceremony’s shabby sets and props.[10] Perhaps so. But thanks to the lively performances of Phelps and the gifted writers and artists who rendered them in print and illustration, the imagination even today has plenty of material with which to work.

Notes

[1] William W. Phelps, Great Salt Lake City, to Brigham Young, October 12, 1863, Brigham Young Office Files, CR 1234 1, reel 54, LDS Church History Library.

[2] See, for instance, Hans P. Freece, The Letters of an Apostate Mormon to His Son (New York: self-published, 1908), 42, https://books.google.com/books?id=JihOAAAAYAAJ.

[3] “Doctor Luther sagte / wenn er des Teufels mit der heiligen Schrifft vnd mit ernstlichen worten / nicht hette können los werden / so hette er in offt mit spitzigen worten vndlecherlichen bossen vertrieben . . . Quia est superbus Spiritus, & non potest ferre contemptum.” Translation from Martin Luther, The Table Talk of Martin Luther, translated and edited by William Hazlitt (London: H. G. Bohn, 1857), lxxxvi, https://books.google.com/books?id=n-IFAAAAQAAJ. See also Parley P. Pratt, A Dialogue between Joe. Smith and the Devil! [1844], https://archive.org/details/dialoguebetweenj00parl.

[4] Brigham Young, July 31, 1853, Journal of Discourses, edited by G. D. Watt, et al. (London: Latter-Day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–1886), 1:170.

[5] Thomas White, The Mormon Mysteries: Being an Exposition of the Ceremonies of “The Endowment,” And of the Seven Degrees of the Temple, 2nd ed. (New York: Published by Edmund K. Knowlton, 1851 [1847]), 10–12. Special thanks to H. Michael Marquardt for informing me of this source’s original publication date and the Van Dusens’ exact endowment date.

[6] “The Mormonites: Affairs in Utah—The Gladdenites—General character of the Mormons,” New York Times, July 19, 1853, 3.

[7] John Hyde Jr., Mormonism: Its Leaders and Designs, 2nd ed. (New York: W. P. Fetridge, 1857), 94, https://books.google.com/books?id=bVVgAAAAcAAJ.

[8] Fanny Stenhouse, “Tell It All”: The Story of a Life’s Experience in Mormonism (Hartford, Conn: A. D. Worthington, 1875 [1874]), 364, https://archive.org/details/tellitallstoryof00sten.

[9] Artemus Ward; His Travels (New York: Geo. W. Carleton, 1865), 193, https://archive.org/details/artemuswardhistr00wardrich.

[10] Ann Eliza Young, Wife No. 19, or the Story of a Life in Bondage, Being a Complete Exposé of Mormonism, and Revealing the Sorrows, Sacrifices, and Sufferings of Women in Polygamy (Hartford, Conn.: Dustin, Gilman, 1876), 365, https://archive.org/details/wifenoorstoryofl00youniala.